Research posters are a multi-modal communication genre combining text with graphics, colour, as well as speech and interaction with audience, to convey meaning. Posters are useful because they convey meaning efficiently, and they can facilitate more informal discussions between presenters and peers than other research communication modes. Posters are typically used in the sciences, but they may also be used in the social sciences. They may be used in academic conferences as well as workplaces or other settings.

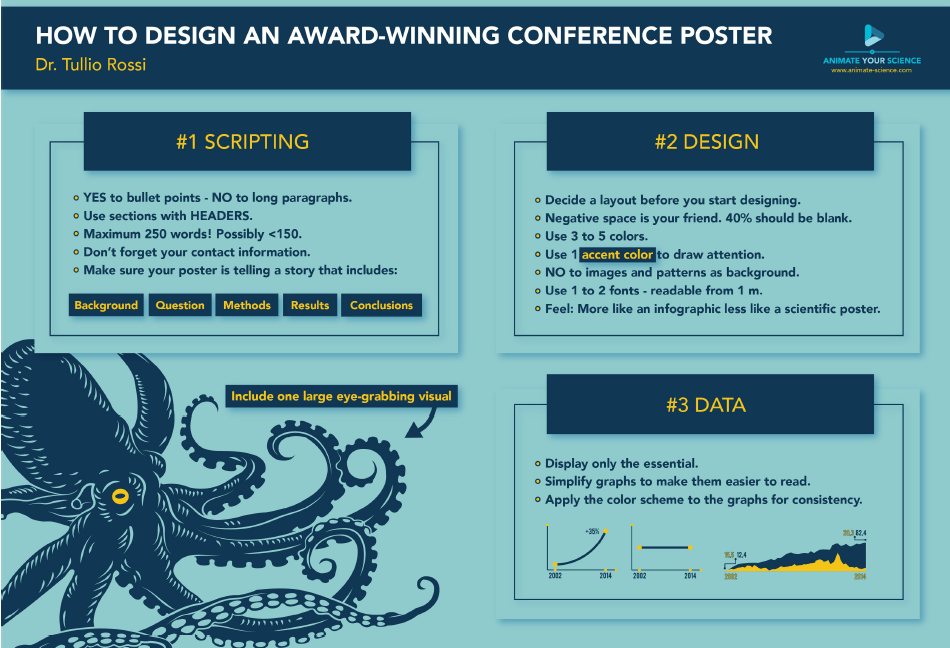

Posters should convey the meaning on their own, and, when verbally explained by presenters, their meaning should be communicated economically, enabling discussion beyond the immediate outline of the research. There are three aspects of a good poster presentation: visual display and organisation, research content, and the presenter's attentiveness and communication with viewers. Some tips and resources for designing and presenting an effective poster are provided below.

Ensure key information can be comprehended in approximately five to ten minutes (less than 1000 words).

Research posters follow the same story line as all research communication. The order of content is as follows:

Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop and InDesign are good for posters, including lots of high-resolution images, but they are more complex and expensive.

OpenOffice Impress is a free alternative to PowerPoint in MS Office.

Inkscape and Gimp are alternatives to Adobe products.

Gliffy or Lovely Charts are good for charts.

Glog is a visual learning platform that enables text, graphics, images, wallpaper, audio, video and web ($29 for individuals, $390 for 10 teachers/250 students).

University of Brighton https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/visuallearning/visual-communication/ and https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/visuallearning/finding-images/

Colin Purrington : http://colinpurrington.com/tips/poster-design

Block, S.M. (1996). Do's and don'ts of poster presentations. Biophysical Journal 71, 3527-3529.

Bracher, L., Cantrell, J., & Wilkie, K. (1998). The process of poster presentation: a valuable experience. Medical Teacher 20, 552-557.

D'Angelo, L. (2010). Creating a framework for the analysis of academic posters, Language Studies Working Papers, 2, 38-50.

Denzine, G.M. (1999). An example of innovative teaching: preparing graduate students for poster presentations. Journal of College Student Development 40, 91-93.

Hay, I., & Thomas, S.M. (1999). Making sense with posters in biological science education. Journal of Biological Education 33, 209-214.

MacIntosh-Murray, A. (2007). Poster presentations as a genre in knowledge communication. A case study of forms, norms and values. Science Communication 28, 347-376. 50

Matthews, L.D. (1990). The scientific poster: guidelines for effective visual communication. Technical Communication 37, 225-232.

Miracle, V.A. (2003). How to do an effective poster presentation in the workplace. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 22, 171-72.

Naerssen, van M. (1984). Science conference poster presentations in an ESP program. The ESP Journal 3, 47- 52.

Powell-Tuck, J., Leach, S., & MacCready, L. (2002). Electronic poster presentations in BAPEN: a controlled evaluation. Clinical Nutrition 21, 261-263.

Waehler, C.A., & Welch, A.A. (1995). Preferences about APA posters. American Psychologist 50, 727.

Wang, J.C., Yoo, S., & Delamarter, R.B. (1999). The publication rates of presentations at major Spine Specialty Society meetings. Spine 24, 425-427.

Woolsey, J.D. (1989). Combating poster fatigue: how to use visual grammar and analysis to effect better visual communication. Transactions in Neurosciences 12, 325-32.

Wright, V., & Moll, J.M. (1987). Proper poster presentations: a visual and verbal ABC. British Journal of Rheumatology 26, 292-294.